La vie ranci

The world of modern winemaking, where technology, science, engineering, and control are the hallmarks of how wine gets from vineyard to bottle has been challenged by the contemporary philosophies and methodologies of the natural wine movement. From biodynamic farming to low intervention techniques and the eschewing of sulfites and other additives to wine, an embrace of pre-industrial ways of making wine has captured the imaginations of winemakers and wine-lovers alike. It’s more than a back-to-the-roots movement. It’s a reimagining what wine is and should be.

Ranci sec, a wine from the Roussillon, France, embodies the essential ideas of natural wine – and has a long history and tradition that couldn’t to be erased by the forces of capitalism, contemporary rules of commerce or laws and regulations that conspired against its very existence. Through the love and struggle of a handful of individuals, Ranci sec is now recognized and treasured as a Catalan cultural heritage – and the great wine it has always been.

Ranci (rancio in Spanish) directly translated into English means “rancid.” Not exactly a positive description. However, the term ranci carries with the idea of being traditional - and more so of a tradition that takes the idea of letting foods and wines mellow and mature for an overly-long time and allowing that time to create something that defies the vicissitudes of age turning it into a something truly exceptional and delicious.

Born of earth, air, water, sun and time, Ranci sec harks back to how wines were made for millennia around the Mediterranean, yet speaks to the land of Roussillon,

An old maxim describes ranci sec as le goût de soleil, the taste of the sun. But it's a particular type of sun, colored by rolling hills of late summer herbs and grasses, blanched and intoxicating the air with thick, deep perfume. It's a late summer sun, saturated with saline moisture, drifting long and lazy along wild Mediterranean beaches. It's the rays of sun captured over months and years, magnified through hand-blown glass into a living, breathing nectar, changing its youthful insouciance into something much more thoughtful and mature. The color of ranci may range from a deep chestnut, to a blushing peach, to a straw like golden glow. But often there will be glinting overtones of vermillion, catching the fleeting tones of the southern sun at sunset.

And the sun is a major factor in how this wine is made. Grenache Blanc and Maccabeau are the primary grapes used to make Dry Ranci Unlike the more famous and sweeter Rivesaltes wines, Maury and Banyuls, wines that come from the same region, Vi Ranci, with native yeasts, goes through full fermentation, creating a completely dry wine. Sometimes the fermentation will take years. But the main process that makes rancio so unique is its elevage. Rancis, now by law, must be aged for at least five years, either in glass demijohns or in barrels, or a combination o both. One of the most common methods is to fill demijohns with plenty of headspace for air, leaving them outdoors for at least a year. Changing temperatures, intense sun, the vagaries of weather, leave a lasting impression on the fermented and fermenting juice. All the while the wine goes through an oxidative magic, developing intense flavors, reminiscent of nuts and dried fruits. Then the wine is transferred into barrels, where wood, still more oxygen and age transform the wine even more. For at least 5 years! Through this aging, the liquid evaporates, intensifying flavors, aromas, acidity and alcohol.

When the appellation system was put in place in France in 1936, Ranci Sec missed out. The famous fortified sweet wines; Rivesaltes, Maury and Banyuls were defined by strict parameters of production and place. In 1977, Côtes du Roussillon and Côtes du Roussillon Villages became their own AOCs, but the rules for these wines were strictly for creating basic, if some very good, table wines. There was still no room for Ranci Sec. If a winemaker wanted to bottle and market Ranci Sec it could only be described as a Vin de Pays, which told the uniformed, as most consumers were, of what might be in that bottle.

But a few winemakers kept this tradition alive following family traditions – making special batches for themselves and friends. Others discovered that barrel, forgotten in the cellar, tasted it and thought how can I recreate this! This tradition, the knowledge was being passed on, but there was little or no way to bring Ranci Sec to market.

And then Jean Jean Lhéritier came along.

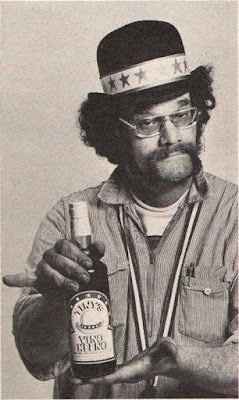

Jean is an affable fellow who laughs easily. He scrunches his bushy eyebrows when making a point and keeps a quiet intensity and focus on his passions, the food and wine traditions of Roussillon.

So he organized and became the first president of Slow Food France mainly to keep these traditions alive and thriving.

His primary mission was to make sure Ranci Sec was recognized.

As he put it, “Ranci Sec didn’t have the right to exist. It wasn’t authorized. And it was more complicated because, first of all, the word ‘ranci’ couldn't be used - because it was given to the union of natural sweet wine [Maury, Banyuls, Rivesaltes] producers. And also, pretty often, Ranci Sec is over 15% ABV and in France when the wine is over 15% it enters into a higher tax bracket - and it leaves the category of ‘wine.’ It’s no longer considered a wine.”

Some ranci secs could be bottled, but they could only be labeled as Vin de France.

“They couldn’t use the domain name, the village name, nothing!” says Lhéritier, still astonished.

He and a group of producers organized put together a two-pronged approach to get Ranci Sec recognized. One was to get it on Slow Food’s radar.

This involved creating Slow Food France in 2003. With an official recognition in the growing international community of foodway protectors and enthusiasts, he, as president, jumped headfirst into his passion project. By 2004, Slow Food established the Rousillon Dry Ranci Wine Presidium with about 15 producers. Now, with the imprimatur of Slow Food International, he and the winemakers were ready to tackle the French wine establishment.

Negotiations began Institut national de l’origine et de la qualite (INAO), the national organization charged with regulating French agricultural projects. Finally, in 2012, the INAO gave Ranci Sec at place at the table with the creation of two new Indication Geographique Protegee (IGP) realms - IGP vin de pays des Côtes Catalanes, Ranci Sec and IGP vin de pays Côte Vermeille, Ranci Sec. The IGP falls loosely between labeling wines “Vin de France,” the catch-all category that covers your basic vine de table, and AOP (Appelation d’Origine Protegee) - wines that are strictly controlled and defined as to how they must be made, what grapes they must contain. Not that the new Rancio Secs IGPs do not have some controls, but now the producers were able to make – and clearly define and market – wines that are considerably different than other types of wines that were already protected by AOC demarcations in the very same area of the Roussillon.

A victory for Lhéritier and the producers of Ranci Sec.

Comments